|

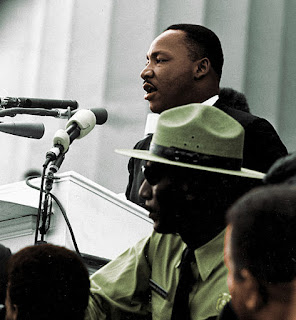

| Martin Luther King, Jr. From the March on Washington, 1963. Government photo: public domain. Colorized photography (2016). Wikimedia Commons. |

NOW my reading on the U-Bahn — which, as it strikes me now, is taking up a strangely large part of recent blog posts — has turned from Voltaire to Henri Troyat and Martin Luther King, Jr. To begin with the second book:

In 1958 King published Stride Toward Freedom, where he describes himself leaving university and deciding where to become a minister, and why, and how he changes the Alabamian church where he and Coretta Scott King decided to begin his ministerial life at the birth of the civil rights movement.

A peculiar phenomenon is that things progress, regress and stay the same in an inconsistent way, all at once. It isn't just the decade that matters, but also the generation. Martin Luther King, Jr. mentions young African Americans rebelling against racist society at a time where African American adults who were educated and well-off sometimes did not want to do anything to risk their jobs or status in society. Years ago the Guardian ran an article ("She would not be moved," Gary Younge) about Claudette Colvin, who remained sitting in the 'wrong' seat of a bus when she was fifteen years old, before Rosa Parks did the same. He mentions her, too. Of course, the right of African American children to attend schools that white children attended had also been recognized in the Supreme Court 5 years before the book was published; girls had walked to school past crowds of rabid adults. Emmett Till was killed around that time. But the bus boycotts, the Greensboro lunch sit-ins, the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, and the Supreme Court's recognition of the right to mixed-race marriage had not happened yet; and churches were bombed later, Medgar Evers assassinated later, and voting rights proponents who were registering African American voters were murdered into the 1960s.

Martin Luther King, Jr.'s writing at that time is self-conscious, I think. Part of it is I think a carefulness not to say anything jarring that can undermine one's public standing or one's 'message.' Whether I think this carefulness should be necessary is another question. But to be wildly optimistic maybe it has more to do with being a political figure in the public eye, than with being the potential target of racists who are eager to find excuses to criticize any African Americans in the public eye.

Ta-Nehisi Coates's article "My President Was Black"* about President Obama for the Atlantic, published in January before the inauguration of Donald Trump, is relevant to that issue, too. I think it's called 'respectability politics,' and the Nation of Islam was a strange example of it in a broader sense; in order to be equal to white men, you had to be rigidly well conducted and attired in suits at all times or in general act like a respectable 1950s paterfamilias. (In the end I think the Atlantic article reflects its writer more than it does the subject, because I think he wants to understand himself through President Obama. Besides, I don't remember if there was anything specifically about feeling the need to be exceptionally self-censoring in the article, except perhaps on Michelle Obama's part, because of the fear that arose in white quarters in 2008 that she was 'too angry.' But I found it absorbing to read anyway.)

* You will probably have to un-block the advertising to read it.

* You will probably have to un-block the advertising to read it.

***

Next: Henri Troyat's Les Désordres secrets (1974). I find the level of precision in his language to be far behind Molière and Voltaire; it's not that he tried to compete with them at all, it's only that I read them recently so that I see a contrast. I think he has also read too much Tolstoy; an author is far more endurable when he is the Narcissus and not the Echo. But I feel a bit mean in saying this, because his own family escaped the 20th century Russian revolution, and clearly Russian literature, history and society were a highly personal matter to him.

Troyat's tale, a fragment of the Muscovite series, begins during the retreat of Napoléon's French army from Moscow, felt through the eyes of an aristocrat(?). Hailing from Gaul, he had been raised in a noble Russian family, so he feels goodwill toward both sides. Part of the aristocrat's cortège, as he is a French soldier retreating from Moscow, is an actress who has become his mistress. Like her theatrical colleagues, Paulette finds the company's programme far more absorbing than the actions and plans of the Russian or French armies or their leaders, or the risk of attack by Russian pursuers. There is a lack of relevance of her thespian concerns to his emotional rift between upbringing and adulthood, etc.

Of course I don't admire the idea of men taking women as companions whom they don't see as mental equals and whom they cannot speak with frankly and fully about important matters. But at least it's funny if one remembers Jane Austen's passage characterizing the phenomenon:

Troyat's tale, a fragment of the Muscovite series, begins during the retreat of Napoléon's French army from Moscow, felt through the eyes of an aristocrat(?). Hailing from Gaul, he had been raised in a noble Russian family, so he feels goodwill toward both sides. Part of the aristocrat's cortège, as he is a French soldier retreating from Moscow, is an actress who has become his mistress. Like her theatrical colleagues, Paulette finds the company's programme far more absorbing than the actions and plans of the Russian or French armies or their leaders, or the risk of attack by Russian pursuers. There is a lack of relevance of her thespian concerns to his emotional rift between upbringing and adulthood, etc.

Of course I don't admire the idea of men taking women as companions whom they don't see as mental equals and whom they cannot speak with frankly and fully about important matters. But at least it's funny if one remembers Jane Austen's passage characterizing the phenomenon:

The advantages of natural folly in a beautiful girl have been already set forth by the capital pen of a sister author; and to her treatment of the subject I will only add, in justice to men, that though to the larger and more trifling part of the sex, imbecility in females is a great enhancement of their personal charms, there is a portion of them too reasonable and too well informed themselves to desire anything more in woman than ignorance. But Catherine did not know her own advantages [...]

I also guess (so far) that Troyat-the-narrator is a more advanced, nicer dinosaur than many others.

***